The Science of Microsoft Certification Prep: A Veteran’s Guide

For anyone working in the Microsoft ecosystem, there can be no doubt that their certifications are invaluable. Beyond offering a chance to develop and prove one’s competence, Microsoft heavily incentivizes its certifications through its Partner Program, strongly motivating many employers to hire (or produce) certified employees. Whether you’re just looking to upskill or trying to make your resume more enticing, Microsoft certifications are a valuable resource for accelerating your IT career.

In the blog that follows, I’ll outline the techniques I developed over my time studying for Microsoft exams, which you can apply in your own studies, along with the science behind why they work.

Answers from Experience

I haven’t always known what to tell people about certification exam prep. Nonetheless, on numerous occasions, someone has looked me up on LinkedIn, seen my number of MS certifications per year, and asked me how I do it. On at least three of these, it was my first time meeting the person, and they had looked up my credentials in advance. On top of this, I’ve had to give presentations to trainees or had colleagues or acquaintances ask for advice on exam preparation.

Needless to say, I’ve had to give the matter a lot of thought. After deep introspection (and reading a lot of cognitive science and pedagogy), my answers have been improving. Certification isn’t a magic trick, and I hope my experience can provide some guidance to others seeking to walk that same road.

I’ve organized my thoughts around the three most common questions. Hopefully, my answers will point you in the right direction.

The questions are:

- How do you find the time?

- How do you remember everything?

- How do you know when you’re ready to take the test?

If you don’t want to read MS Learn:

Before we even begin, some people will object to studying on Microsoft Learn, particularly through the written modules and learning paths. That’s fine, but two things should be mentioned.

- I use Microsoft Learn almost exclusively. That doesn’t mean you have to. Other options include blogs, online videos, study guides, and formal courses (though Microsoft Learn has these, too). My suggestions apply to these other avenues as well.

- That said, innate learning styles are a neuromyth (and yes, these are all separate links). Studies consistently show that students who study in ways that match their preferred style achieve no better results than those who don’t, and in some cases, learning in more challenging ways improves long-term retention. Learning from text, video, practice exercises, etc, is not a natural inclination: It’s a learned skill. If you don’t want to use Microsoft Learn because you don’t think it fits your natural style, then I’m sorry, but you’re wrong.

Q: How do you find the time?

The Problem:

When I first started out, finding time was easy. As a student, I’d finished my dissertation and was waiting for reviewers’ comments and approvals, as one does at that stage. That left me plenty of time to study for Microsoft exams. After I graduated, I had about a year of unemployment. When I started interviewing for the job I finally got, I had earned eleven certifications. I earned another two before starting full-time work in August 2024. Naturally, the pace slowed down after that, but it didn’t stop. I earned 7 additional certifications in 17 months of full-time employment, including 3 advanced (“expert” level) certifications that required considerably more study.

And no, once I started work, I didn’t study off the clock. I’m lucky enough to have an employer who sees studying as part of my job and lets me allocate about 10% of my day to it. Still, that’s not actually where I learn the most (especially during months when, like many knowledge workers, I’m too busy with higher-priority tasks to fill that part of my allocation).

My Solution:

One of my most effective practices has been keeping a Microsoft Learn tab open at all times. Knowledge work is full of stops and starts. Whether it’s waiting for a solution to export, a pipeline to finish running, or a customer to finish typing/not typing/typing a reply, there are inevitable gaps and pauses. During these moments, I switch over to the Microsoft Learn tab. Sometimes I read only a sentence, sometimes a paragraph, and sometimes (when the pipeline takes around ten minutes, which is still too short to meaningfully work on another job), even a page or more. And yes, sometimes that means reading the same sentence more than once if it didn’t stick the first time. It’ll sink in eventually, and those small gains count. When the day is done, consider finishing the current page before you log out.

Note that this is not the same as multitasking! Multitasking is the process of rapidly switching between two or more tasks, attempting to do them simultaneously while actually alternating between them. Multitasking costs more time than it saves due to the time and energy required to switch between processes, and it has numerous other downsides as well. Avoid it! Swap to that Microsoft Learn tab only when you cannot do anything else.

Don’t worry if you only finish a single page today, and most of that is done before you log out. The important thing here is the “little bit a day,” not the timing. Studying doesn’t have to involve marathon cram sessions. Make a habit of learning regularly in small doses.

The Science:

There are three key insights that suggest why this approach is effective:

- Habit stacking: Behavioral psychology supports the idea that we develop new habits most easily by linking them with old ones. In this case, it means associating that slow IT process with studying Microsoft Learn materials instead of whatever you currently do (which is probably reaching for your phone).

- Microlearning: Pedagogical studies have found strong support for microlearning, the learning approach championed most notably by lightweight online platforms like Duolingo. Studies suggest that microlearning can make information easier to absorb, improve long-term retention, and reduce learner fatigue (which is important when you’re saving your mental energy for the “real” work).

- Spaced repetition: Since the 1800s, scientists have demonstrated that repetition of new concepts over time improves our memory of them, to the point that it’s treated as a point of common sense. Nonetheless, evidence continues to mount that learning on a regular basis, with gaps, is far more effective than learning large amounts of information all at once, just as studying every night in school always outperformed the all-night cram session.

Q: How do you remember everything?

The problem:

We’ve all been there. You’re tired, and the words on the page flow right through you. You finish a paragraph or even just a sentence, having no idea what you’ve just read. Or perhaps you finish a whole chapter of a book, thinking you’ve understood, but the next day, the few pieces you’ve retained don’t even fit together. It’s not a fun experience, and it can quickly be discouraging when you’re trying to master a new subject on your own.

When I first started out, I really didn’t remember much, and the parts I did were disconnected facts and details without important context. My first few months on the job involved a lot of connecting abstract pieces of information and making them work for me. Figuring out how to retain information has been a hard-fought battle, and most of my techniques have been stumbled upon by accident. If you’re in the same boat, don’t despair. Most likely, you’ve just been reading (or listening or watching) without processing. Never fear: This is an easy problem to fix, but the details depend a bit on the type of material you’re working with.

My Solution:

As I see it, new material has basically three levels of difficulty. That level has as much to do with your background as the material itself. Either you know most of it already, you know the background, or you know nothing about it. For each level, the optimal strategy differs:

Type One: The Familiar Subject

Difficulty:

Experience:

Strategy:

Explanation:

Easy

“I already know this.”

Just keep reading

Good learning material is often adapted to accommodate learners of specific backgrounds and levels of expertise, but no two learners of the same level have the same knowledge, so the material will never fit perfectly. It might be tempting to skip easy sections. Don’t.

New information may hide in the gaps, and it never hurts to review the basics. Ensure you have a good foundation for the parts that aren’t so simple.

Type Two: The New Material

Difficulty:

Experience:

Strategy:

Explanation:

Medium

“This is new.”

Read and process internally.

This is your sweet spot for studying new material, where you’re learning new things every paragraph while also knowing enough about the topic to understand what you’re taking in. Ideally, all material would be like this. When you hit your stride like this, it can be tempting to plow through. Resist that temptation! Good learning and retention happen not from your brain taking in new information but from processing and using it, making connections to other ideas. Fortunately, this level of material only requires internal processing. Pause periodically to imagine applying these new skills or explain them to someone in your head. Putting the knowledge to work, even in this small way, cements the connections and makes the information clearer in your mind. Without it, you’re likely to get to the end of the module and realize you’ve already forgotten important bits.

Type Three: The Enigma

Difficulty:

Experience:

Strategy:

Explanation:

Hard

“What is this even talking about?”

Process externally while reading.

In any learning effort, there inevitably will be material that doesn’t match your background. Don’t panic, don’t blame yourself, and above all, don’t quit. Such material takes more effort on your part, but it can also be the most satisfying when it finally clicks. To make this work, however, you need to move from internal to external processing, some of which will necessarily happen while you read. This takes more than just thinking hard. You need to go slow, look up unfamiliar concepts, get help from outside sources (such as other material, friends, colleagues, or even your favorite AI), and then apply that knowledge outside your brain. This means doing things like practice exercises, writing down your thoughts, or explaining it to a colleague (or at least a rubber duck). Even talking it over with a chatbot can help you put the ideas in order (Note that this should be an active discussion on your part, not just asking the bot to explain it again from scratch. A good pattern is: “Do I understand correctly that. . .?” “Are you sure? But then how does that relate to. . .?” “I see. So, in other words. . .”). Looking up background material, explanations, and definitions as you go along transforms the material into something closer to Type Two, and then the external processing helps you cement the ideas and helps you review your understanding to ensure the facts you collected make sense.

The Science:

Applying knowledge, even in mental simulation, creates an advanced form of what scientists call “Active Recall,” a potent study method that strengthens the connections around a concept in your brain by actively applying it rather than just hearing or reading it. This relates to the testing effect, the cognitive effect in which retrieving information (such as for a test) solidifies it in memory more securely than simply taking it in. The more advanced form of active recall recommended here, in which information is actively applied to multiple related subjects, evokes what educational psychologist Merlin C. Wittrock called “Generative Learning Theory.” According to Wittrock’s theory, your goal in processing your reading is to:

- Recall what you’ve learned

- Connect it to what you’ve learned before

- Organize your knowledge

- Elaborate on your learning using your prior knowledge

The above strategies are what I’ve found effective for that, but others accomplish the same thing by testing the information, blogging about it, or using other strategies (including explicitly walking through the four steps above). The important thing is to apply the information to your existing knowledge and toward some goal (even a made-up one, like explaining it to someone in your head).

Q: How do you know when you’re ready to take the test?

The Problem:

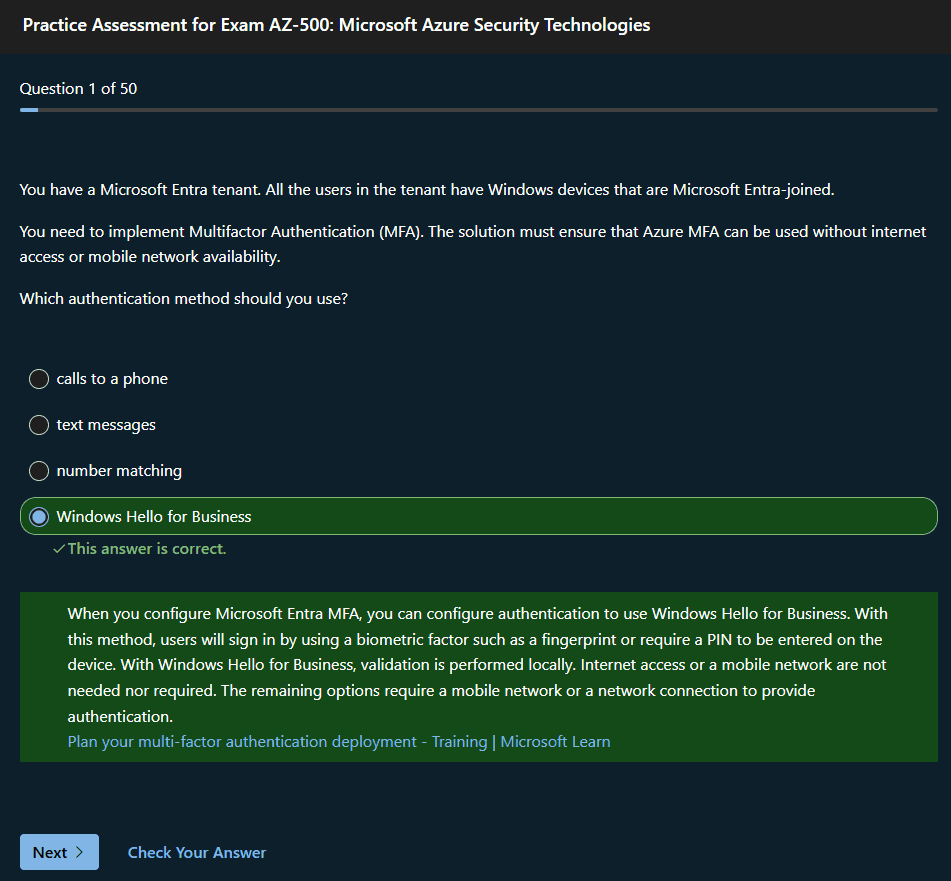

Microsoft has a clear guideline for this one, actually: If you consistently get 80% or more on the practice exam over multiple attempts, you’re ready.

That said, only for my first exam, Azure Fundamentals, did I ever stop there, and many people don’t feel confident in going in based on that alone, so it’s fair that I get asked this sometimes. For those seeking to go further, Microsoft additionally provides other recommendations and materials to prepare for exams.

My Solution:

The following may be overkill, but I find overpreparing for exams pays off when it’s time to do the actual work, and as a bonus, I haven’t failed an exam yet.

My usual approach is to:

- Read all Microsoft Learn material in the study plan, often digressing into related modules and learning paths when the urge strikes. Exam preparation isn’t a race, so feel free to take your time and browse a bit.

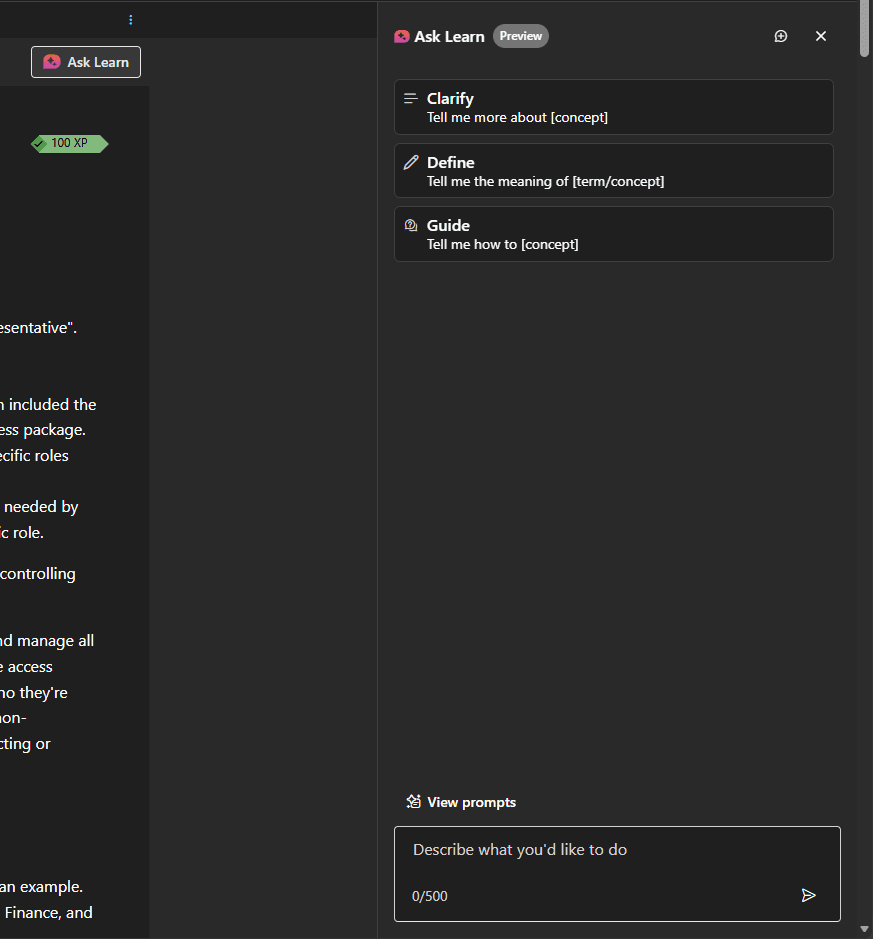

- Study the practice exam explanation links. Rather than taking the practice exam for its own sake, I click the button to check my answer for each question, then read all the linked material the answer provides, and do further reading if I still don’t understand why that was the right answer or all the concepts involved. If my practice exam has a failing score, I take the recommended learning plan and read anything in it I haven’t already read. I then repeat the process until it feels like I’ve read all the material linked to the practice exam. Note that using the practice exams in this way aligns with the intended user flow.

If there is no practice exam or learning paths, such as when taking a beta exam (I’ve only done this once so far), I turn to the official study guide. I read down that until I find something I don’t feel I have good working knowledge of, and then read Learn modules until I feel differently. This seems to work just as well, but I haven’t tested it broadly.

For a good selection of Microsoft exam prep video resources, see the Microsoft Exam Readiness Zone.

The Science:

If only there were a scientific way to measure this one. Alas, the exams were made by comparatively non-deterministic humans, so “what the exam giver thinks is worth asking” is always going to be up in the air. Nonetheless, there are some tricks you can rely on during the exam process.

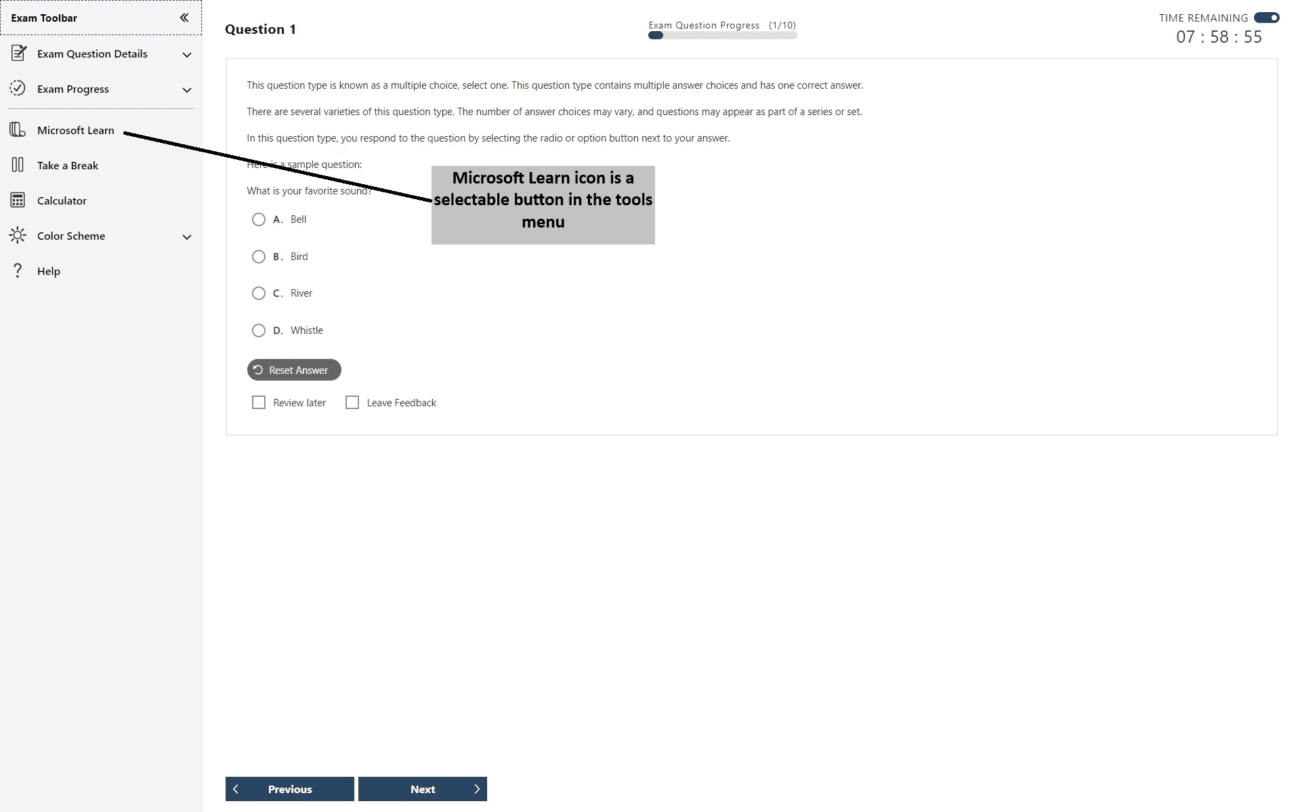

The biggest of these is that, except on Fundamentals exams, Microsoft Learn is available within the exam interface. Get to know the search there before the exam! Learn what types of searches get the most relevant results (usually full sentences rather than keywords – the AI-backed search engine will use those semantic relationships to its advantage) or trigger the AI summary (usually single concepts or full names of services), and you’ll find what you’re looking for much faster. Microsoft providing this almost feels like cheating sometimes, but it’s also a good reflection of real working conditions. Just like in the real world, you can look things up in the docs, but you need to know enough to know what to look for.

Remember, though, that time is limited. Even with the best searching, you can’t answer all the questions from Microsoft Learn within the time limit, and you need to understand enough to know what to search for. Access to the Microsoft Learn page is not a substitute for studying, and you’ll be missing key features (like the ability to use CTRL+F to find text on the page) when you use the website in exam mode.

After that, all the usual tricks for multiple-choice exams apply (process of elimination, etc.). You don’t need to memorize everything (or anything, really). Being ready to take the exam is about understanding the concepts and how they work together in practice.

What NOT to do:

About the worst approach to earning Microsoft certifications you can possibly take is memorizing exam dumps. Aside from the ethical concerns (using exam dumps is against Microsoft’s exam terms and conditions) and quality concerns (while exam dumps typically have enough right answers that you’ll pass, they mix in plenty of wrong ones, so you can’t actually trust any competence you gain that way), you should be wary of ever earning any certification without also developing the related competence.

The more credentials you earn, the bigger this concern becomes. The last thing you need is to be hired based on your certifications and then asked to do a task on day one that is covered by a cert you didn’t properly study for. Revealing that you lack that skill set undermines trust not only in that one certification of yours but in all of them. After all, if you earned that without learning the basics, who’s to say you earned the others any differently? The more certifications you earn, the more cred you stand to lose. Keep your focus on learning the material. The certifications themselves are just convenient milestones.

Conclusion:

Studying new technology is unavoidable, especially if you work in IT, and the Microsoft certification program provides a good roadmap for achieving a wide breadth of competence within Microsoft’s ecosystem. Nonetheless, it isn’t always easy. Still, dividing work into small batches, taking time to process your learning, and knowing when you’re ready will go far toward helping you prepare for your next exam. Stick to it.